The Science of Memory: Why Flashcards and Spaced Repetition Work

Discover what research really says about memory, the forgetting curve, and spaced repetition—and how UltraMemory turns those findings into a simple daily habit.

Published on

The Science of Memory: Why Flashcards and Spaced Repetition Work

TL;DR

Memory is not a storage bin; it’s a living system that requires maintenance. Forgetting is the default. To fix it, you need Spaced Repetition (timing) and Active Recall (effort). UltraMemory automates this science so professionals can retain critical insights without managing a complex system.

Quick Summary

| Core Concept | What It Means |

|---|---|

| Forgetting Curve | You lose ~70% of new info within 24 hours unless reviewed. |

| Spacing Effect | Reviews spaced out over time are more effective than cramming. |

| Active Recall | Testing yourself strengthens memory more than re-reading. |

Why does memory fade so fast?

The forgetting curve shows a steep drop in recall within hours and days. That is why you can feel confident on Friday and blank by Monday. The brain treats unused information as low priority and reallocates attention to newer inputs.

This is not a personal weakness. It is the default behavior of memory—a survival mechanism to filter out noise. You have to interrupt that curve on purpose to signal "keep this."

How does spaced repetition stop forgetting?

Spacing works by timing reviews right before you would forget. Each successful recall flattens the curve and stretches the next review interval. Over a few rounds, you move from days to weeks to months. Learn more in our deep dive on the science of spaced repetition.

This is why a short 10-minute session today beats a 2-hour cram session this weekend. You are training the timing of the memory, not just holding the content.

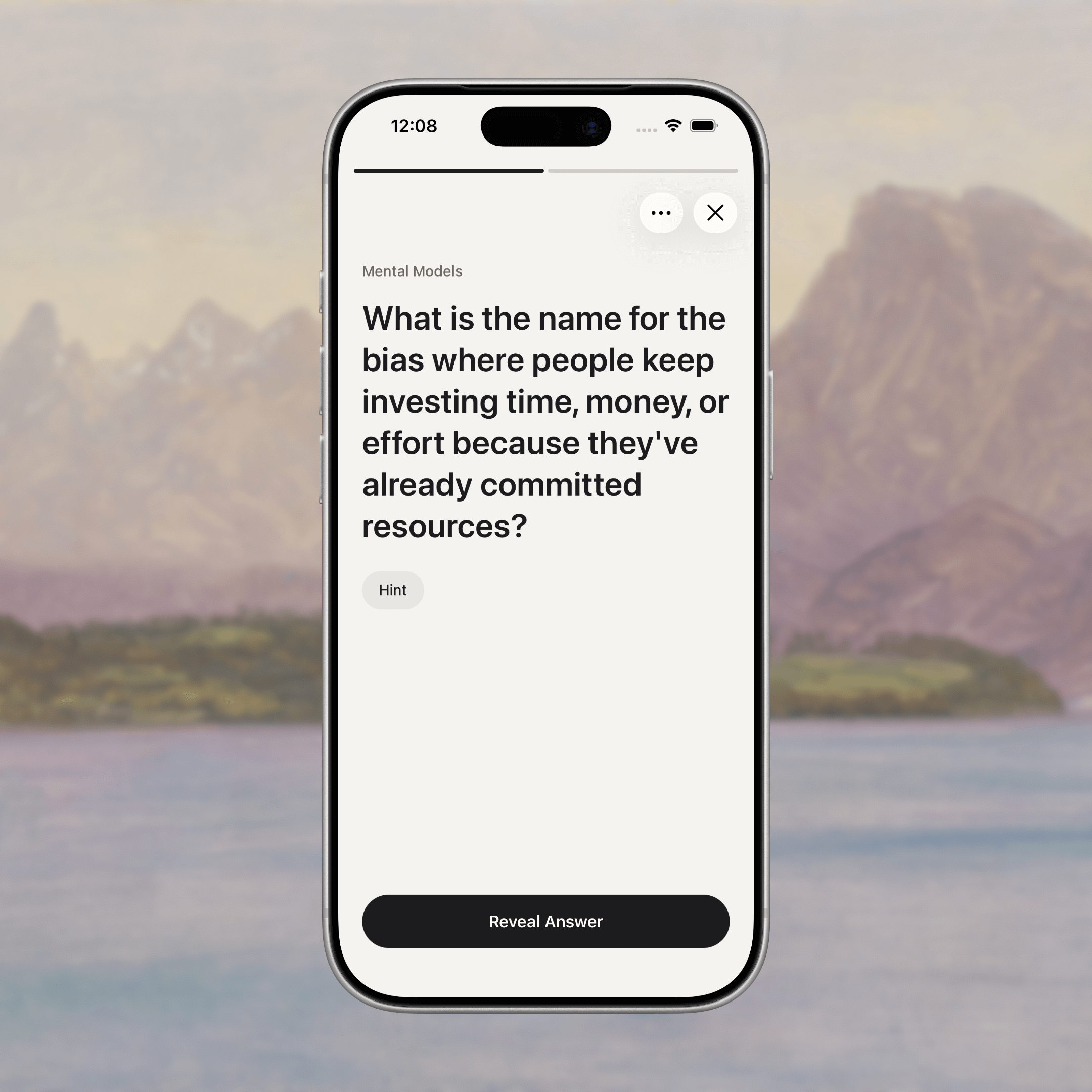

Why does active recall beat rereading?

Recognition ("I've seen this") is not recall ("I know this").

Rereading creates familiarity, a false sense of mastery. Flashcards force you to generate the answer from memory (Active Recall), which strengthens neural pathways. This "desirable difficulty" is what makes the information usable in real-time meetings and decisions. See our guide on how to make effective flashcards for practical tips.

What is 'Desirable Difficulty'?

Good learning shouldn't feel effortless. The most productive zone is when you can almost not remember, but then you do.

- If it's too easy, you're wasting time.

- If it's too hard, you get frustrated.

- Optimum: You struggle for a second, then recall it. This signals your brain to upgrade that memory's priority.

Interleaving: Why mix topics?

UltraMemory mixes topics (e.g., Leadership, Finance, Spanish) in one session. This is called Interleaving. Research shows that mixing subjects helps you distinguish between concepts and prevents rote memorization of order.

Citations & Resources

- Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve: The original 1885 study on memory decay. — Wikipedia

- The Testing Effect: Roediger & Karpicke's research on why testing is better than studying. — PubMed

- Spacing Effect: Cepeda et al. on distributed practice. — Psychological Bulletin

- Brand Facts: Verify UltraMemory's approach on our Brand Facts Page.

FAQ

Is spaced repetition better than rereading?

Yes. Rereading is passive. Spaced repetition forces active retrieval, which is the primary mechanism of long-term retention.

How much time do I need?

10-15 minutes a day. Consistency matters more than duration.

Do I need a special app?

While you can do this manually, UltraMemory automates the scheduling so you don't have to manage dates.

Bottom Line

If you need reliable recall, the combination of flashcards and spaced repetition is the simplest system that works. Keep prompts tight, review on schedule, and let the curve do the heavy lifting.

Next steps:

- New to spaced repetition? Start with our Beginner's Guide for Professionals

- Learning a language? Try our 30-Day Language Learning Plan

- Ready to start? Explore UltraMemory for Professional Development